Report of the Medical Department of the

Pan-American Exposition, Buffalo, 1901

By Roswell Park, M.D., Buffalo, N.

Y., Medical Director

Buffalo Medical Journal December 1901

The subjoined report of the workings

of The Medical Bureau of the Pan-American Exposition Company is submitted

for the information and use of the Board of Directors and all others who

may desire to refer to it. This bureau was really organised during midsummer

of 1900 by the appointment of the writer as medical director and the recognition

of the department as an independent one, the director reporting only to

the executive committee and the director-general. The writer was given

free power in the selection of his assistants and in operating his department.

He was informed that the sum of $20,000 had been appropriated for the expense

of the department from its inception to the close of the exposition. Out

of this, the hospital was to be equipped and all the running expenses paid.

Organisation being the first requirement,

he selected Dr Vertner Kenerson as deputy medical director, Miss Adella

Walters, a graduate of the Buffalo General Hospital, as superintendent,

and Miss Minnie A. VanEvery, who was to act in combined capacity of stenographer

and trained nurse. About the 1st of September, 1900, four rooms in the

Service Building were assigned for the use of the department. It was not

long before it appeared necessary to have a resident physician who should

be available for service at all hours of the night and day, since more

or less night work was going on, and there was always a liability to accident.

Accordingly, Dr. Alexander Allan was selected and took up his residence

in the Service Building a couple of weeks later, Dr. Eli Schriver, Jr.,

substituting for him for a short time. From the 1st of September, 1900,

until the 1st of May, 1901, these rooms were made to suffice for the purpose.

Most of the cases attended during this time were of the nature of minor

injuries, there being occasional cases of illness, and very few serious

accidents. During this construction period, 750 people received "first

aid" attention in these temporary apartments.

As the season for opening the exposition

grew nearer, more detailed plans for caring for visitors were required.

Accordingly, a small area between the Service Building and the West Amherst

gate was selected as an appropriate site for the hospital. It was intentionally

placed near the gate in order that it might he more easily approached by

carriages and ambulances from without, as also because there was ready

access to the street cars. Plans for the hospital building were prepared

by the medical director and Mr. Weatherwax, the chief draughtsman in the

Service Building. These provided for three wards, two for men and one for

women, with accommodations for 25 beds, with a complete operating room

outfit, suitable offices, accommodations for nurses and resident physicians,

and sheds for ambulances. Descriptions of this building have already been

published and it is perhaps hardly necessary here to go into detail. Suffice

it to say that a practically complete small hospital was erected and equipped

with everything needed for the purpose. A part of the purely surgical equipment

was loaned by The Jeffrey Fell Company, of this city, as a part of their

exhibit, and to them this department is under many obligations for courtesies

and assistance of this kind.

The Wagner Company also supplied, in

the same way, a large static machine with an x-ray outfit, and numerous

smaller exhibits were sent in for use by various individuals and firms.

Operating table, ordinary sterilising appliances and instruments were provided

at the outset by the Exposition Company.

The department force and physicians

was now increased by several important appointments. Dr. Nelson W. Wilson

was appointed sanitary officer, and at once entered upon an exceedingly

active campaign, which resulted in a sanitary condition of affairs which

was noticed by almost every visitor to the Exposition. More will he said

about these sanitary arrangements below.

During the first month of the Exposition

period, the roster of the hospital was as follows: Dr. Roswell Park, medical

director; Dr. Vertner Kenerson, deputy medical director; Dr. Nelson W.

Wilson, sanitary inspector; Miss Adella Walters, superintendent; Miss Minnie

VanEvery stenographer and trained Nurse; Drs. F. Zittel, Alexander Allan,

Geo. McK. Hall and E. C. Mann, house staff: Messrs. B. J. Bixby, Bert Simpson,

T. I,. Ellis and Norman S. Betts, ambulance men and male nurses.

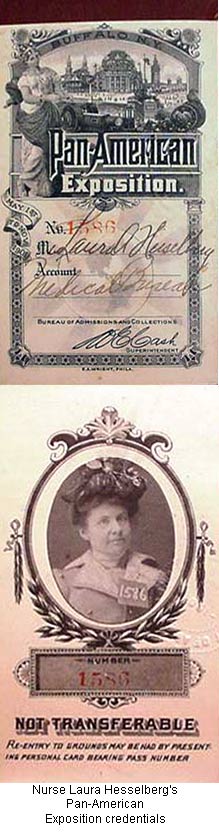

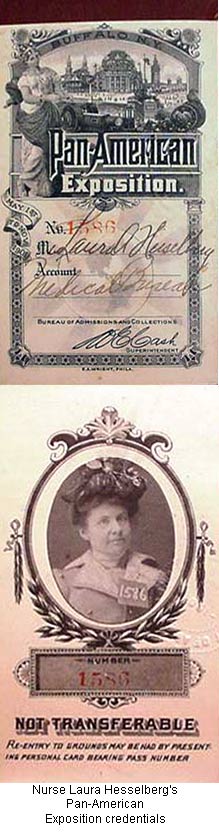

The

May nurses were: Mrs. Laura Hesselberg,

Presbyterian Hospital, New York; Miss Claribel Lichtenstein, La Tour Infirmary,

New Orleans, La.; Miss Cecil Dodge, Chicago Baptist Hospital. Chicago, Ills.;

and Miss Margaret Haines, Buffalo Children's and Woman's Hospitals, Buffalo,

N.Y.

The

May nurses were: Mrs. Laura Hesselberg,

Presbyterian Hospital, New York; Miss Claribel Lichtenstein, La Tour Infirmary,

New Orleans, La.; Miss Cecil Dodge, Chicago Baptist Hospital. Chicago, Ills.;

and Miss Margaret Haines, Buffalo Children's and Woman's Hospitals, Buffalo,

N.Y.

June nurses: Misses A. L. Greenwood

and Miss Florence Hamilton, Buffalo General Hospital; Miss Laura Jarvis,

Arnot Ogden Hospital, Elmira, N.Y.; Miss Eleanor Alexander, Kingston, Ont.,

and Miss Mabel Farnsworth, Buffalo.

July nurses: Miss M. McCulloch, Lansing

hospital, Lansing, Mich.; Miss Jennie Wanner, Garfield Memorial Hospital,

Washington, D.C.; Miss Maud Trueman, Royal Victoria Hospital, Barrie, Ont.;

Miss Hattie Cary, Buffalo General Hospital; Mrs. Eunice Hughes, University

of Maryland Hospital; and Miss Dodds, Lexington Hospital, Buffalo.

August nurses: Mrs. Anna Richmond,

Hants Infirmary, London, Eng.; Miss B. Jelly, London, Ont., General Hospital;

Miss Teresa Bartle, St. Luke's Hospital, Chicago, Ill.; Miss J. B. Downing

and Miss Katherine Simmons, Roosevelt Hospital, New York, and Miss Mae

Railton, Buffalo General Hospital.

September nurses: Miss K. Simmons,

(2nd month) in charge of Creche, Roosevelt Hospital, New York; Miss Dorchester,

Buffalo General Hospital; Miss Baron, Long Island College Hospital, Brooklyn,

N. Y.; Miss Shannon, Spanish War Nurse anti General Memorial Hospital,

New York; and Miss Morris, St. Luke's Hospital, New York.

October nurses: Miss M. L. Davidson,

Long Island College Hospital, Brooklyn, N. Y.; Miss Anna Hadden, Orange

(N. J.) Training School, Orange, N. J.; Miss Charity Babcock, Johns Hopkins

Hospital, Baltimore, Md.; Miss M. Michell, Jewish Hospital, Cincinnati,

O.; and Misses M. Conners and McLaren, Rochester City Hospital.

Arrangements had been perfected during

the preceding months for ample supply of nurses, as well as for their selection

from various schools in the country. A circular of information was prepared

and sent out, inviting applications and informing applicants that their

applications for one month tour of duty would be received, and that for

these services they would be given all the privileges of the fair, with

ample opportunity off duty to see all that was to be seen, and that they

would receive also $25 each as a mere honorarium intended to cover their

traveling expenses, and the like, in addition to their board and laundry.

Over I50 requests from all parts of the country were received. From these

selection was made, as above, those serving for each month being indicated.

A housemaid was also added and served in the diet kitchen.

The rule was laid down positively, first of

all, that there was to be no charge for services rendered, and that these were

to be only of the first aid order, patients being kept only long enough to enable

them to leave the building or the grounds in suitable condition. The rule was

also made that no patients were to be kept over night, but were to be sent to

their homes, to the railroad stations, or to some other

hospital, as they might elect or the circumstances might require. This rule

was disregarded only in one or two instances in the case of some of the resident

population who had no place to go, or who could not be accompanied by an interpreter.

Suitable badges were provided for the

three principal medical officers, of gold or silver, and for all the hospital

corps of silver, with the red cross as a prominent feature, by which their

wearers were enabled to pass, at all times, to all points within the grounds.

All the male members of the hospital corps were dressed in suitable blue

uniforms for cold weather, and white for warm weather, and every nurse

when on duty wore the uniform of the school from which she graduated.

The Exposition guards were instructed

to recognise the badges of the medical corps and to render such assistance

and cooperation as might be called for at any time. On numerous occasions

they were of no small assistance.

The Medical Department was given jurisdiction

over all the sanitary arrangements of the grounds and matters pertaining

to public health. This included supervision of the houses of public comfort,

all the sewerage and drainage arrangements of the grounds themselves, the

foods served in all the restaurants, the soft drinks in the various restaurants

and concessions, and everything that pertained to public health. How carefully

these sanitary arrangements were attended to will be evidenced by the fact

that few, if any, cases of illness due to lack of any precautions have

ever come to our knowledge. Not a few persons suffered from over-indulgence,

but so far we have learned no one suffered from improper character of food,

save in the instances to be referred to below, of the Indian children who

were made sick by eating decayed fruit thrown out from the Horticultural

Building.

The hospital building was placed in

perfect telephonic communication with all parts of the grounds and nearly

all of the ambulance calls which came in were reported over the telephone.

A pay roll was sent in every month, having upon it the name of every employee

of the department. No one was asked to do work for nothing, and every one

was paid for his or her work exactly as per the original agreement.

Early in the progress of the fair it

had been suggested to establish a Creche. By resolution of the directors

this was not done, however, until August, when large tents were erected,

cots provided, and one of our nurses detailed for this especial work. A

nursery maid was also employed. For the care of children in the Creche

a nominal charge was made of 25 to 50 cents, according to the time they

remained, and these were the only fees or money accepted by the department

during its entire service. The Creche proved to be very popular, and during

the hot weather of August and early September, was well patronised. It

a little more than covered the actual outlay it required.

The original intention was to have

three ambulances, one of each type -- electric, gasoline and steam. It

was found, however, that none of the manufacturers using gasoline engines

made an ambulance, and the Rochester firm which promised a steam motor

vehicle failed to keep their agreement. Consequently, the only ambulance

maintained upon the grounds throughout the season for our work was that

of the Riker system, furnished by The New York Electric Motor Vehicle Company.

This was put in commission before the opening of the fair as an exhibit,

and, during the season, made many hundreds of trips of various lengths.

Not once did it disappoint us in its reliability and constant availability,

and while I feel that we are under very many obligations to the company

which furnished it, I cannot speak in too high terms of its efficiency.

The water supply to the grounds and

buildings was ample and always reliable. The water supply of the City of

Buffalo being at all times exceptionally good, we had but very little to

contend with in the matter of pollution from this source. Several attempts

were made to create newspaper sensations at a distance front Buffalo, and

to make it appear that exposition visitors had contracted typhoid upon

our grounds. Every one of these, however, when investigated, proved to

be purely sensational and without foundation.

The sewerage of the grounds was also

excellent, and we had very few complaints on this account. We were met

more than half way by the city authorities whenever it was necessary, and

I may say at this point that there was throughout the whole period the

heartiest cooperation between the City Health Department, with its various

officials, and ourselves. Health Commissioner Wende extended many courtesies

to us in this regard.

A very complete set of hospital records

was kept. In a large book were entered the name, age, temporary and permanent

addresses of every patient, along with the nature of the trouble for which

he came to the hospital, and also the final disposition of the case. Aside

from this, a duplicate card record was kept, which included the number,

as taken front our large book, the name, residence, the city address, hour

and date of admission and of discharge, the name of the employee, if the

patient were an employee, the method of his admission, i.e., whether he

came by ambulance, rolling chair, stretcher or on foot, the moment when

the ambulance call was received, and the moment when the patient was delivered

at the hospital, diagnosis, brief note of treatment, and a statement regarding

the final disposition of the patient. One set of these cards was filed

for our own reference and use and the other was sent daily to the Committee

of Law and Insurance, so that every night the legal authorities of the

Exposition knew just what accidents had been cared for, or possible liabilities

incurred through the day. This was an extremely valuable feature of our

work and saved much trouble. Our own card records were preserved in alphabetical

order, as well.

From the outset, I insisted that patients

coming to us for help should be treated with every courtesy and with becoming

privacy. During the earlier weeks of the fair, I had considerable trouble

with reporters from various papers who exhibited an undue and unbecoming

anxiety to get what they considered news and construct out of the items

given them more or less sensational reports. The rule was laid down, and

strictly adhered to, that no names should be given out without the consent

of the individuals concerned, that our records were private, that our hospital

was a retreat and an asylum to which those who were sick and injured could

come when they desired for refuge from the public, and that from this rule

there should be no departure. The local manager of the local press made

himself peculiarly offensive in protesting against this rule, but it was

nevertheless adhered to and the riot act was read to him on more than one

occasion.

Herewith are submitted statistical

tables, from which sufficient information may be gleaned as to the general

character of our work, number of cases, etc. The tables will be self explanatory

and probably need no further comment:

TABLE 1

Classified List of Cases No2. 1

to 5,573

| Continued and eruptive fevers |

17 |

| Malaria |

7

|

| Rheumatism |

75 |

| Diseases of nervous system |

162

|

| Diseases of circulatory system |

180

|

| Diseases of respiratory system |

223

|

| Diseases of digestive system |

1,971

|

| Diseases of lymphatic system |

14

|

| Diseases of urinary system |

20

|

| Diseases of generative system (male) |

15

|

| Diseases of generative system (female) |

45

|

| Diseases of skin . |

111

|

| Diseases of and injuries to the eye |

247

|

| Diseases of ear . |

28

|

| Diseases of chest |

12

|

| Diseases of throat |

205

|

| Heat exhaustion |

55

|

| Exhaustion (other) |

51

|

| Syphilis |

5

|

| Burns and scalds |

97

|

| Minor injuries and wounds |

1,482

|

| Scalp wounds |

80

|

| Sprains |

758

|

| Dislocations |

5

|

| Gunshot wounds |

6

|

| Electric shock |

3

|

| Intoxication |

4

|

| Toothache |

1,614

|

| Teeth extracted |

43

|

Fractures

-

Fracture of radius . . . . . . . . . 4

-

Fracture of clavicle . . . . . . ... 2

-

Fracture of fingers . . . . . . . .. 7

-

Fracture of nose . . . . . . . . . . 7

-

Fracture of arm . . . . . . . . . ..11

-

Fracture of skull . . . . . . . . . ..

4

-

Fracture of leg . . . . . . . . . .. .

7

-

Fracture of foot . . . . . . . . . ...

2

-

Fracture of ribs . . . . . . . . . . ..6

-

Fracture, Potts's . . . . . . . . ..

1

-

Fracture of toes . . . . . . . . . ..

3

-

Fracture of femur . . . . . . . .

. 2

|

78 |

| Deaths in Pan American hospital |

4

|

|

Total

|

5573

|

TABLE II

Deaths in Pan-American Hospital

and Ambulance

Case No. 2,226: Pneumonia

Case No. 4,775: Apoplexy.

Case No. 5,557: Heart Disease.

Death in ambulance of man shot during

a fracas in the Free Midway.

Baby in Indian Village, died of entero-colitis,

treatment being refused.

Premature birth (6 or 7 mos.) in African

Village.

Indian baby died, in hospital, of

inspiration pneumonia, following inspiration of some grains of partially

cooked rice.

Deaths By Accident On The Grounds

One man killed by cars before Medical

Bureau was organised.

Case No. 613: Struck by Belt Line

train; both legs severed from body. Killed instantly.

Case No. 631: Fracture of skull. Killed

instantly.

Case No. 3,490: Bullet through sternum.

Killed instantly.

Case No. 3,565: Fracture of skull.

Killed instantly.

Two men killed by electricity. Not

taken to hospital.

TABLE III

Births

Two births in Indian Village. One birth

in Filipino Village.

TABLE IV

Totals of Patients by Months

| August, 1900 |

17

|

April, 1901 |

167

|

| September, 1900 |

60

|

May, 1901 |

482

|

| October, 1900 |

86

|

June, 1901 |

660

|

| November, 1900 |

94

|

July, 1901 |

1,018

|

| December, 1900 |

73

|

August, 1901 |

1,145

|

| January, 1901 |

92

|

September, 1901 |

954

|

| February, 1901 |

59

|

October, 1901 |

554

|

| March, 1901 |

l00

|

|

|

|

|

TOTAL |

5,561

|

Total for construction period up to

May 1, 1901 . . . . . ........ 748

Total for Exposition period up to

November 1, 1901 . . … .4,813

Daily average for construction period

. . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Daily average for Exposition period

. . . . . . . . . . . . ……….26

TABLE V

Number of Patients Sent to Each

Hospital

| Buffalo General |

36 |

| Homeopathic |

8

|

| German |

2

|

| Riverside |

2

|

| German Deaconess |

1

|

| Sisters |

21 |

|

Total

|

70 |

Summary

Total number of diagnoses . . . . .

. . . . . . . . 5,572

Total number of persons killed . .

. . . . . . . . . . 4

Total number of patients treated .

. . . . . . . . . . . 5,567

Total number of cases with more than

one major injury . . 9

Further details regarding

the sanitary inspection of the grounds may be of interest. Much of what follows

I have epitomized from the monthly reports of Dr. Wilson, the sanitary inspector.

During the earlier part of the fair period two daily inspection tours of the

Midway and one of the grounds and buildings were made. Suitable blanks were

prepared and sent in to medical headquarters each day, reporting the extent

and time of inspection and the results. One of these blanks showed, at a glance,

the daily condition of the Exposition; another gave a list of the places inspected

each day; another was served on exhibitors and concessionaires on whose premises

any sanitary nuisance existed. In this last those at fault were given a certain

number of hours for the correction of the nuisance, while failure on their part

to comply with the order within the time limit resulted in the work being done

under the supervision of the sanitary officer and the expense charged against

the premises. At the conclusion of the necessary work, reinspection was made,

and another blank filled in with details and sent to the medical director. During

the month of May, for instance, 68 nuisance notices were served, and in only

one instance was it necessary to call upon the Superintendent of the Exposition

Street Cleaning Department to remedy the fault. Some trouble was met with in

that portion of the grounds occupied by the Indian Congress, where the land

lay low and where the Indians lived in tepees, which, after the heavy rains

of the month, once or twice became almost uninhabitable. In this case the concessionaires

voluntarily raised the ground, and the sanitary bureau provided an extra drain,

and thus the fault was remedied.

Early in May, or very shortly after

their arrival, the Esquimaux in the Esquimaux Village developed an epidemic

of measles, of which there were, in all, eleven cases. The village was

quarantined and a guard stationed at the gate. The cases were transferred,

as they- occurred, to the contagious pavilion of the General Hospital,

and quarantine was maintained until May 30. Mumps also appeared in the

Hawaiian Village, but prompt quarantine checked a spread of the disease

An important part of the work was the

regulation and supervision of the milk and cream supply. In every place

on the grounds where these articles were on sale the source of supply was

learned, and it was ordered that neither of them should be bought from

any source save a dealer subject to the City Health Department regulations.

When concessionaires did not live up to these requirements, delivery of

goods was stopped. Careful inspection of meat and ice boxes and supplies

of this character was practised from the beginning, and not a few times

bad ice was condemned. Some difficulty was met with in the beginning in

ensuring proper cleaning of the tumblers at many of the stands where soft

drinks were sold. This was mainly due to the lack of running water at these

points.

Every water closet for men was in charge

of a male attendant, and a woman was placed in charge of each woman's toilet

room. Directions were given which preserved almost absolute cleanliness,

and throughout the season there was very little ground for complaint on

this score. By the first of June, there were in operation on the grounds

over 500 closets and urinals, a map showing the former being kept constantly

on file at the Medical Director's office. As warm weather approached, every

restaurant was required to furnish the name of the dealers supplying milk,

cream, ice cream and meats, and the ice boxes and refrigerators were carefully

watched.

In July it became necessary to keep

careful watch on the Indian Congress because of the susceptibility of the

Indians to tuberculosis. During this month eight were returned to their

reservations and the quarters occupied by them thoroughly cleaned and disinfected.

In the Filipino and African Villages it became necessary to put up health

notices in more than one language, and to issue very positive instructions

to managers and interpreters, especially regarding the proper use of ordinary

toilet and sanitary provisions. Our principal trouble was to maintain reasonable

cleanliness among the inhabitants of The Beautiful Orient. Only after continuous

and constant pressure was it possible to get them to keep their stables

and yards reasonably clean. More than once it was necessary to seize rotten

fruit sold at the fruit stands in the Streets of Cairo. The inhabitants

of this concession seemed to be absolutely incorrigible, and incapable

of appreciating the ordinary laws of health.

During the month of July, there were

29 restaurants open and doing business, and 43 stands at which soft drinks

were sold. The resident population for the month was -- people, 1,535;

animals, 607. Food supplies were frequently inspected on receipt, but about

the only time when it was necessary to order food thrown out was one occasion

in August at a restaurant in the Beautiful Orient. About the only influence

which could be effectually brought to bear on the people in this concession

was a threat to close up the business. The other concessions gave very

little trouble. Once at the Filipino Village an old woman well advanced

with pulmonary tuberculosis was found at work stripping tobacco for the

cigar makers. She was promptly removed front the tobacco room and directions

given regarding the disinfection of her sputum. During this month of August

also an Indian baby died at the hospital of inspiration pneumonia, which

was not due to exposure, but to trouble following inspiration into the

lungs of some grains of partially cooked rice.

By the end of July there were 36 restaurants

and eating places, 14 kitchens on concessions and villages, and 57 soft

drink stands, and the resident population had increased to 1652. That the

residents of the concessions lead adopted stricter sanitary pleasures was

evident from the fact that during this month it was necessary to issue

only 43 time-limit notices threatening condemnation for failure to correct.

Alter a while, the regular hours of inspection were abandoned and the inspections

were made at irregular and intentionally unexpected intervals in order

that no preparation for them could be made. The results of this change

were an evident improvement in all sanitary conditions. In no case during

August was it necessary to condemn milk or cream, and only one eating place

gave any serious trouble. This was the Nebraska Sod house, which was all

almost constant source of bother and which later had to be closed. Night

inspections revealed the fact that many people were in the habit of sleeping

beneath the counters in booths in various streets. The practice was stopped,

for instance, of making of candy in a booth in which a family of four lived,

cooked, ate and slept.

On the 9th of August an Indian child

was taken seriously ill. Treatment by the medical department was refused

and the Indian medicine plan took charge of the case. The child died within

twenty-four hours. Investigation showed that the death of this child and

the serious illness of two others were due to the fact that the Indian

children were in the habit of eating fruit which their parents had secured

from the Horticultural Building, which fruit was discarded because it was

no longer fresh nor presentable. It was hard to impress the Indian parents

with the idea that this trouble was due not to the "anger of the Great

Spirit," but to disregard of common hygienic laws. Dr. Wilson, however.

succeeded in impressing them with the idea that it was rotten fruit which

"the Great Spirit" did not like to have them eat. During this month also

four more Indians mere returned to their reservations on account of tuberculosis.

A mild epidemic of barber's itch appeared

upon the grounds, which was traced to barber shops outside, where a number

of guards and attendants were in the habit of being shaved. Suitable treatment

of individuals and suitable instructions at the barber shops soon checked

this difficulty. By the end of august the number of people living on the

grounds was 1,703, and the number of animals 1,255.

A little ripple of excitement was caused

by newspaper statements, that eight persons coming from Newark, N.J., had

contracted typhoid fever at the Exposition. It appeared, on careful examination,

that typhoid was prevalent in Newark at the time these people left home,

and it was easy to see that their typhoid was contracted before they came

to Buffalo, although it may not leave appeared until after their return

home.

In September, national calamity led

to the closing of the Exposition on three different days. It was naturally

expected that there would be temptation to keep food supplies too long

and it became necessary to condemn a number of supplies of meat and other

food, as well as of milk and cream. Every restaurant and every kitchen

was carefully inspected prior to reopening and where there was any doubt

condemnation was enforced.

The Beautiful Orient continued to give

more or less trouble, and on one evening visit twelve people were found

occupying one small room. It was cleared and disinfected, and the practise

prohibited. It became necessary to return three more Indians to their reservations,

one had a broken arm, the others were suffering from tuberculosis. A mild

outbreak of measles occurred in the camp of the United States Marines.

The cases were sent to the hospital and tents and quarters were thoroughly

fumigated. During September a few cases of milk fever were reported among

the animals of the Live Stock exhibit. They were properly cared for by

a veterinarian, and the disease did not spread. During September, the largest

resident population was met with, namely, 1792.

During the closing months of the fair

there seemed to be temptation to carelessness on the part of some of the

concessionaires and vigilance was redoubled. While it was necessary in

a number of instances to condemn food during this month, there was but

one known instance of serious trouble which might have been charged to

negligence in this respect. This was the case of a young woman who was

taken acutely sick on the grounds, and who died later at the General hospital.

A careful investigation showed that she ate little or nothing upon the

grounds, and that, although she seemed to die of ptomaine poisoning, it

was not due to anything which she had procured within the Exposition limits.

During October, four more Indians were sent home. At the conclusion of

the Exposition period - namely, on the second day of November, all sanitary

supervision of the grounds, and the like, was formally transferred to the

City Health Department, and the operation of this bureau, in this and all

other respects, were completely suspended.

The expenses, of the Medical Bureau

ran up to a total of $16,332.72. This included all the moneys which were

paid out for any purposes connected with the bureau, household equipment,

drugs, running expenses, and Creche. This amount includes $4,832.80 expended

previous to May 1, and $11,499.92 expended between May and the close of

the Exposition. The cost of the hospital was $6, 966.54.

A brief study of the weather conditions

during the Exposition period may be of interest at this point. It is made

up front the records of the Weather Bureau. The mean temperature of May,

1901, was 54 degrees, the coldest in four years, while the precipitation

was 3.28, which made it the wettest May in seven years. In June, the mean

temperature was 54°, which made it the coldest June in the history

of the Weather Bureau in 30 years, while the precipitation was that for

the preceding month, making it the wettest June in seven years. From this

there was an abrupt change to reverse conditions. The mean temperature

for Judy was 74 degrees, which was only equalled during the past 30 years

by two other Julys, while the precipitation was 3.05. August also was warm,

but with a light rainfall, which made altogether a beautiful month. September

was quite wet during the middle of the month, and its temperature seemed

above normal. October proved to be the coldest October in five years, with

a mean temperature of 53 degrees. During the fair period of 1901, there

were 68 wet days. During the previous year and the same period there were

59 wet days. Briefly summed up, the Exposition furnished us with weather

to which quite appropriately Mr. Cuthbertson has applied the terms "rainy.

raw, chilly, hot, cold and cloudy", with a notable infrequency of clear

days, all which had its effect in discouraging and disheartening would-be

visitors to the fair.

If it were the place, a number of things

might be said pertaining to the humorous side of the situation. People

persisted in mistaking us for a free drug store and trying to get all sorts

of prescriptions filled without expense to themselves. They also came in

on all sorts of absurd errands, even occasionally soliciting baths. One

night when I was at the hospital a negro carne in from " Darkest Africa,"

and, with the utmost seriousness, demanded a dose of poison. As nearly

as we could gather from him, this was intended for one of his confreres

in the Negro Village with whom he had had a quarrel, and he announced that

it was his intention to give him poison rather than club him or stab him,

because he thought a natural sort of death would attract less attention

than a more conspicuous homicidal attempt.

Of course, by all means the most important

work of the medical bureau was connected with the Presidential tragedy,

about which so much has already been said that it does not seem necessary

to more than allude to it here as part of the work of the bureau. Had it

not been for the existence upon the grounds of such a hospital as we had,

ready for any such event, it would not have been possible to give the President

the advantage of such prompt intervention as that which was afforded. As

it was, I have often repeated the remark, which I made during that sad

week to numerous members of the government, that "because of what we had

provided upon the grounds the President was not deprived of the of the

benefits of private citizenship," as he would have been under most

other circumstances. The existence of the hospital and the workings of

the medical bureau were certainly justified at this time beyond all expectations

or desire.

I ought not to close this report of the workings

of the Medical Department without, both gracefully and gratefully, acknowledgments

first to the Directors, the Director-General and the Director of Works, to whom

I never appealed in vain, and, secondly, to my assistants and staff of helpers,

all of whom rendered most cheerful and most effective assistance. Dr. Kenerson

was of greatest service, especially during the organisation period, when his

readiness and skill in managing details appeared to best possible advantage.

To him and to Dr. Wilson, whose services I have already mentioned, I feel very

greatly indebted. To the members of the hospital staff, especially to Dr. Zittel,

I feel that very much credit is due, and to the nursing staff who served throughout

with zeal and fidelity, I feel particularly grateful. For over a year Miss Walters

managed the details of the nursing, as well as of household cares, with rare

tact and faithfulness, and it would be unfair not to comment most favorably

at this point on her work. One and all, however, assisted, each to the best

of his or her ability, and the result was a department of which, as the Director-General

said, there had been and could be no complaint.

Doing

the Pan Home

The

May nurses were: Mrs. Laura Hesselberg,

Presbyterian Hospital, New York; Miss Claribel Lichtenstein, La Tour Infirmary,

New Orleans, La.; Miss Cecil Dodge, Chicago Baptist Hospital. Chicago, Ills.;

and Miss Margaret Haines, Buffalo Children's and Woman's Hospitals, Buffalo,

N.Y.

The

May nurses were: Mrs. Laura Hesselberg,

Presbyterian Hospital, New York; Miss Claribel Lichtenstein, La Tour Infirmary,

New Orleans, La.; Miss Cecil Dodge, Chicago Baptist Hospital. Chicago, Ills.;

and Miss Margaret Haines, Buffalo Children's and Woman's Hospitals, Buffalo,

N.Y.