|

By Lillian W. Betts The Outlook September 14, 1901 |

|

After everything is said of the beautiful Pan-American Exposition

at Buffalo, the most wonderful sight there is the people. Every

section of our own country is represented, while the foreigners,

especially the Spanish Americans and Cubans, are constantly in

evidence. The tongue of every civilized nation is heard, while

the accent of every section of our own country shows how far-reaching is the interest of our people in this Exposition, the

patriotic impulse of which is fully appreciated before the most

careless of visitors has spent a day on the grounds. The early

morning is most interesting. The crowds from the night trains

come directly to the grounds, usually laden with hand-baggage and

boxes, and in large parties. Tags on bags and boxes prove that

every State each day sends its full quota of visitors.

That economy must control the expenditures of the majority is fearlessly, openly declared to any observer. Every moment one's country grows dearer, one's respect grows stronger for our magnificent people, as he watches this army of workers moving from building to building, from statue to statue, from garden to garden -- here a party of teachers, there a group of mechanics, there a party of farmers and their wives and children. All are alert, all students, all learners. Every minute is an opportunity to see, to learn, to enjoy. How bravely and gayly the crowds enter the gates in the morning! The exhaustion of a night's travel -- not always in a Pullman, as the toilets made under difficulties testify -- has disappeared. There is no consciousness of bundles or wraps or baggage. The moment has come for which sacrifices have been made, which has been anticipated for months. The Pan-American Exposition lies before them in all its beauty. Consultations are the order, once inside the gates. Which direction will most quickly meet the anticipations? which repay most quickly the sacrifices that made this moment possible? Whatever may be said of previous Expositions, this is the Exposition of the people. Here and there are evidences of wealth; but the mass of the visitors to the Pan-American are the people who work with hands and head to earn their daily bread. The shoulders rounded over the desk, the laboratory, the book, the plow, are all there, telling their stories of service, giving the history of their owner's contribution to this epitome of American civilization. As noon approaches the feet move more slowly, lines appear in faces which in the morning were wreathed in smiles, the searching, questioning expression of the morning is giving way to bewilderment. So much has been seen; and the consciousness of how much more remains to be seen has sapped mental and physical strength, and every bench, every nook where a seat is possible, is taken. The first day there is a struggle to overcome the diffidence of eating in so public a place. This disappears rapidly, for mother-love yields before the importunity of a hungry child. Boxes are opened, and the family group, or the group of friends, are soon chatting, comparing notes, making comments, arranging for the afternoon. Here is a group of three women -- tall, angular, severe. One wonders if anything but glue could make every hair, every line of the dress, from the hat down, assume and keep such absolutely rigid lines. There is a remoteness from the crowd about them that is not the remoteness of mere strangeness, but that which comes from lives lived apart from life. They look as though one more step were impossible. Each carries a box neatly wrapped and tied. They sit down in the shade of the beautiful electric building. Even to sit down in the shade is so grateful that they look at one another in enthusiastic silence. The crowds pass and repass. Soon every seat near them is taken. All about people are eating, children are being fed, the popcorn boy is shouting his wares. The three saints from the unknown land of Quiet look at each other, at the untied boxes in their laps, at the unconcerned lunchers all about them. There is no use; they never can eat so publicly. The tallest, the thinnest, the most rigid of the three speaks. One flash of unspoken admiration from either side into her face; the three rise, turn the bench around, and, facing the building, with their backs to this stream of life, they eat their lunches, happily forgetful of the public.

No exhibit commands more appreciative attention than that of the United States Government. The most ardent advocate of economy in the expenditures of public money would have to admit that the money spent by the National Government in the Pan-American Exposition was money well invested. The exhibit is thoroughly intelligent, well placed and discriminated. Every department of the Government is expressed logically; even the scientific display is kept within the reach of the mind of the average layman. Whether it is an exhibition of the hospital corps, or the gun practice with the great guns, or the display of pure foods, or photographs of agricultural or horticultural specimens in health and disease, the result is in the highest degree educational. The calling into service of the stereopticon, the cinematograph, the phonograph, in the exhibit of the Department of National Education, is a source not only of keen pleasure but of educational value. The little room at all hours visited was crowded. The impulse given to industrial and manual training through the exhibits in the buildings of the Government and the States and in those devoted to the Latin-American exhibits will bear immediate fruit. A woman stood with some friends and her own two half-grown children before the exhibit from the schools of Chili. "My lands! look at that! Our children could not do that. I'm just ashamed of our school when I see what other places have done. We've got to wake up." The interest in Cuba and its people is manifested by the crowded rooms filled with slowly moving people every hour the building is open, and no part of the exhibit arouses more interest than that of the schools, which is comprehensive and well arranged to tell its own story. Both Cuba and the Philippines are centers of vital interest and careful examination. However disastrous and shocking war and its consequent horrors are to our people, one inevitable result follows -- a broadening of knowledge, of sympathy, of interests in and for other peoples. The exhibits from these two territories express the character and aim of their peoples; they were a revelation to our people, and will compel closer attention to the methods evolved at Washington for colonial government. The Pan-American has done more to hasten the day when war will have become one of the crudities of undeveloped civilization than all the declarations of principles and vituperations that have made and divided political parties, putting off the day of universal peace. Peace hath her victories No less renowned than war, and the Pan-American is one.

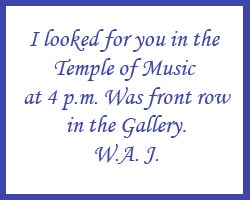

In one of the State buildings every evening a special effort is made to draw together the people of the State who are visiting the Exposition; this is due to the efforts of one of the State Senators present who is deeply interested in the Exposition. Hurried invitations were sent out one noon to a barn dance to be given in the State building that evening. Gray hair, age, and care forgotten, neighbors and friends long sundered, young men and maidens, sons and daughters of these friends, were introduced, and the barn dance under electric lights was a success. The building is admirably designed for purposes of entertaining. A large room with smaller rooms adjoining, broad balconies and veranda, provided for quiet conversations as well as dancing. The spirit of homogeneity developed is perhaps best in evidence in the programme of one evening entertainment at the building of one of the Western States. A resident of a Southern State gave two dialect stories and a negro sermon, the daughter of one of the Commissioners for Honduras a piano solo, as did also a señorita from Puerto Rico. A flute solo was given by a resident of San Domingo, in addition to music and an address by residents of the State. One afternoon the people in this part of the Exposition grounds gathered till verandas, rooms, and the grounds about were crowded with people listening to a lady singing. She had sat down at the piano to gratify a friend who had not heard her sing in many years. They were almost alone in the room when she began. The hush that fell on the crowds on the piazzas of the buildings near by, the silently gathering crowds who stood in the room and outside until the singing ceased, after the singer had responded to many encores, the keen enjoyment cordially expressed to the singer, made an impromptu musicale attended by friends. The Midway is interesting always, but especially so in the evening. Its incongruity is perhaps its chief charm. Here, amid surroundings that suggest everything but America, wander people of every age and condition of life. Darling old ladies whose lives are devoted to the church and its missions saunter from show to show, not missing an audible or visible evidence of the foreign lives imitated so well here. Sitting in the restaurant of one of the foreign villages on the upper floor just as the sun was sinking, the ear and heart were stirred by the sweet silver tones of a cornet. "Abide with Me" floated out on the evening air. The Midway was crowded. The hideous "barkers" had ceased for a moment. The crowds stood still. The accompaniment was softly and sweetly played by a string orchestra. "Rock of Ages" followed. The player was a woman in the dress of a Japanese in the balcony of that village. One seemed a part of a dream. Below, Turk and Caucasian, Indian, African, Eskimo, and imitators of all, could be seen. As the sunset gun was fired from Fort Niagara "America" was played, and the hum of thousands of voices, modulated so well that the silver notes of the cornet kept them in tune, thrilled the listeners in the room far above it all. The Stadium is the center of interest daily; contests of all kinds are held here. Bicycle races, ball games, tennis, foot races, all draw the people. It seats 12,000. On Army Day, when General Miles was the guest of the Exposition, three times this great arena held over 15,000 people. Tier on tier around the great expanse the people waited. When the soldiers appeared, what a roar of applause! It broke out again and again. When, in the late afternoon, the cadets from West Point entered the arena for dress parade, the enthusiasm of the multitude was a tribute to the Nation that produced such men. For that multitude had been observing the "West Point boys." They had seen the gray uniformed figures escorting about the grounds proud, hard-working fathers and mothers, and happy, proud sisters. Fathers and mothers had made sacrifices to fit the "boys" for the place they were now occupying. Each youth represented a contest in which he had come out victor; each one maintained his place by hard work, for one of the strongest of the educational exhibits at the Pan-American Exposition is the day's work required from these cadets. It was all this that added a new note to the enthusiastic welcome accorded them on Army Day at the Exposition. The Temple of Music is another Mecca for the people. The building holds hundreds during each of the two daily concerts, while hundreds more, from lack of time, leave regretfully between the numbers of the programme. This is possible without interruption, as the doors are closed through the rendering of each number of the programme.

But the spell is not broken. The thousands stand transfixed. Was there ever such a sight as this wonder of light and beauty and comradeship? Night after night the same miracle is wrought. North and South, East and West, and the land beyond the seas stand together patriots and brothers, each conscious that a spark of that Genius of Man that has made this moment possible lies within himself, that he is a contributor to the moment. Each goes forth a man of wider sympathies, with a clearer comprehension of the spirit of the civilization of which he is a part. Many men of many nations stand here together. Each will be a better citizen under whatever flag he claims protection, because he has had born within him a new conception of what it is to serve his country as one in the brotherhood of nations made visible at the Pan-American Exposition. |

Back to "Documents and Stories"

Back to "Doing the Pan Home"

Were there ever so many husbands and wives with gray hair

gathered together before! Was there ever seen before such

constant evidence of deep-abiding love, strengthened by the years

of life spent together, as is seen every day as one wanders

through these buildings and grounds! Here, in the shadow of the

pylons, on the bridge facing the electric tower, sits a man whose

form is old but whose heart is young. In his lap is the head of

his wife, covered thinly with gray hair twisted into a tight

knot. Two gaitered feet are stretched out on the bench. Hands

knotted and brown, sharp shoulders covered by the loosely fitting

dress, tell the story of a lifetime of hard work, as the attitude

tells of perfect love. She is sound asleep, though it would only

be dinner-time at home. That husband and guardian knows full well

how unconventional this is, but his expression is trying to tell

you that there is nothing unusual in this afternoon nap in the

sight of a passing public; his expression would shield her from

even the mental comment of the observers. Later in the day they

were seen in the Midway. The wife's eyes were bright, her cheeks

pink as a girl's. Whatever pleasure came to that husband came

through the pleasure of his wife. Nor was he alone in this

attitude of mind. It was seen constantly. The family as it is

seen at this Exposition is the finest product American

civilization has to show.

Were there ever so many husbands and wives with gray hair

gathered together before! Was there ever seen before such

constant evidence of deep-abiding love, strengthened by the years

of life spent together, as is seen every day as one wanders

through these buildings and grounds! Here, in the shadow of the

pylons, on the bridge facing the electric tower, sits a man whose

form is old but whose heart is young. In his lap is the head of

his wife, covered thinly with gray hair twisted into a tight

knot. Two gaitered feet are stretched out on the bench. Hands

knotted and brown, sharp shoulders covered by the loosely fitting

dress, tell the story of a lifetime of hard work, as the attitude

tells of perfect love. She is sound asleep, though it would only

be dinner-time at home. That husband and guardian knows full well

how unconventional this is, but his expression is trying to tell

you that there is nothing unusual in this afternoon nap in the

sight of a passing public; his expression would shield her from

even the mental comment of the observers. Later in the day they

were seen in the Midway. The wife's eyes were bright, her cheeks

pink as a girl's. Whatever pleasure came to that husband came

through the pleasure of his wife. Nor was he alone in this

attitude of mind. It was seen constantly. The family as it is

seen at this Exposition is the finest product American

civilization has to show. On the human side of the Pan-American Exposition the State

buildings are, on the whole, the most interesting centers. In

these buildings people gather with a sense of ownership. You can

distinguish the aliens by the way they enter one of these

buildings. The early morning is the most interesting time. The

travelers by the night trains have arrived. Parcels and lunch-boxes are checked, toilets made, and then people register. These

registers are in three columns, "Name," "Birthplace," "Present

Address." As the home visitor turns these pages after

registering, there are exclamations of delight, invariably, "Why,

So-and-so is here. I haven't seen him since I went to school."

"There! I am so glad, So-and-so was here last week, and he or she

lives at -----. I'll write at once." Each State building provides

post-office facilities, and the broken threads of friendship are

soon knitted together. Then the unexpected meetings! Scarcely a

quarter of an hour passes that does not reveal old friends in

unexpected meetings. Sometimes two will watch each other for

several minutes, and one then decides to ask, "Are you not So-and-so?" usually followed by quick grasping of hands. The sights

and sounds of the moment are forgotten, and the two, or groups to

which the two belong, are living over again the days of childhood

and youth.

On the human side of the Pan-American Exposition the State

buildings are, on the whole, the most interesting centers. In

these buildings people gather with a sense of ownership. You can

distinguish the aliens by the way they enter one of these

buildings. The early morning is the most interesting time. The

travelers by the night trains have arrived. Parcels and lunch-boxes are checked, toilets made, and then people register. These

registers are in three columns, "Name," "Birthplace," "Present

Address." As the home visitor turns these pages after

registering, there are exclamations of delight, invariably, "Why,

So-and-so is here. I haven't seen him since I went to school."

"There! I am so glad, So-and-so was here last week, and he or she

lives at -----. I'll write at once." Each State building provides

post-office facilities, and the broken threads of friendship are

soon knitted together. Then the unexpected meetings! Scarcely a

quarter of an hour passes that does not reveal old friends in

unexpected meetings. Sometimes two will watch each other for

several minutes, and one then decides to ask, "Are you not So-and-so?" usually followed by quick grasping of hands. The sights

and sounds of the moment are forgotten, and the two, or groups to

which the two belong, are living over again the days of childhood

and youth. The climax of the day for every one is eight o'clock in the

evening. As early as seven o'clock the crowds begin to gather in

the Court of the Fountains, the Esplanade, on the Triumphal

Bridge. The band from the Carlisle Indian School takes its place

in the East Stand on the Esplanade. The light of day dies out of

the sky. The soft gray of evening falls over the Tower, domes,

and turrets; with it voices grow soft and low. Who can picture

that multitude? There a group of swarthy men and women tell of

southern suns; there a group, tired, worn, but alert, with

rounded shoulders, sunburned skins, loosely fitting clothes,

broad-brimmed hats, tell of fields and barns; there a group of

Japanese in American clothes, over yonder a group of Chinese with

hands crowded into pockets, stand huddled apart from the crowd.

There on a bench sit four Turks in bagging trousers fezes, and

gold-trimmed jackets. Here stands a man carefully dressed, whose

every movement bespeaks power. College girls, working-girls,

soldiers, cadets, officers, and hundreds and thousands from the

ranks of American men and women are gathered waiting. The few

lights on the posts have disappeared, and semi-darkness envelops

the scene. Pink dots appear everywhere. The Tower is softly

luminous, the light coming from within; arches, domes, roofs,

windows, columns, capitals, statues, are outlined by those pink

dots of light. Softly but clearly the notes of the "Star-Spangled

Banner" float on the air. The people sitting rise, hats are

removed; here and there a head is bowed; one feels the thrill of

thousands of hearts moved by one great emotion. The dots of pink

have now become lines of soft radiance growing whiter each

minute. Strong and full are the notes of a song that, under the

influence of the time, is a nation's anthem. So perfectly timed

is this wonder of light that its fullest radiance is reached as

the last note of music dies away.

The climax of the day for every one is eight o'clock in the

evening. As early as seven o'clock the crowds begin to gather in

the Court of the Fountains, the Esplanade, on the Triumphal

Bridge. The band from the Carlisle Indian School takes its place

in the East Stand on the Esplanade. The light of day dies out of

the sky. The soft gray of evening falls over the Tower, domes,

and turrets; with it voices grow soft and low. Who can picture

that multitude? There a group of swarthy men and women tell of

southern suns; there a group, tired, worn, but alert, with

rounded shoulders, sunburned skins, loosely fitting clothes,

broad-brimmed hats, tell of fields and barns; there a group of

Japanese in American clothes, over yonder a group of Chinese with

hands crowded into pockets, stand huddled apart from the crowd.

There on a bench sit four Turks in bagging trousers fezes, and

gold-trimmed jackets. Here stands a man carefully dressed, whose

every movement bespeaks power. College girls, working-girls,

soldiers, cadets, officers, and hundreds and thousands from the

ranks of American men and women are gathered waiting. The few

lights on the posts have disappeared, and semi-darkness envelops

the scene. Pink dots appear everywhere. The Tower is softly

luminous, the light coming from within; arches, domes, roofs,

windows, columns, capitals, statues, are outlined by those pink

dots of light. Softly but clearly the notes of the "Star-Spangled

Banner" float on the air. The people sitting rise, hats are

removed; here and there a head is bowed; one feels the thrill of

thousands of hearts moved by one great emotion. The dots of pink

have now become lines of soft radiance growing whiter each

minute. Strong and full are the notes of a song that, under the

influence of the time, is a nation's anthem. So perfectly timed

is this wonder of light that its fullest radiance is reached as

the last note of music dies away.