William H. Holmes, Head Curator

When plans were required for an anthropological exhibit to form part of the Government's display at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, 1901, it was, not difficult to decide as to what portion of the very wide field included in the Museum department should be selected. The Pan-American concept furnished the suggestion, and it was arranged to present in the most striking manner possible a synopsis of the Pan-American aborigines, the native peoples of America, from the Eskimo of North Greenland to the wild tribes of Tierra del Fuego. The most salient ideas, or features available for exposition presentation in this field are (1) the peoples themselves, and (2) the material products of their varied activities.

Groups of Lay Figures

The most important unit available for illustrating a people is the family group -- the men, women, and children, with their costumes, personal adornments, and general belongings. It was therefore decided to undertake the preparation of 12 lay-figure family groups, inustrating such tribes as would serve best as types of the ethnic provinces distributed between the northern and southern extremes. With such a set of groups geographically arranged upon the exhibition space it was conceived that the student, and even the, ordinary visitor, might, by passing from north to south or from south to north through the series, form a vivid and definite notion of the appearance, condition, and culture of the race or peoples called American Indians, the race so rudely and completely supplanted by the nations of the OId World. Each lay-figure group comprises from four to seven individuals, selected to best convey an idea of the various members of a typical family, old and young of both sexes.

Two of these groups, the Greenland Eskimo and the Patagonian, occupy cases 8 by 12 feet in horizontal dimensions and stand at the northern and southern extremities of the exhibit. 'The other cases are smaller and accommodate from three to six figures. Each member of a group is represented as engaged in some suitable occupation. The activities of the people are thus inustrated and the various products of industry are, as far as possible, brought together in consistent relations with the group.

In building these figures the closest possible approach to accuracy was sought, building satisfactory costumes were not always available, and collections inustrating arts and industries were found to he deficient, save in a few cases. It is therefore felt that, the exhibit is not yet complete and that many changes win be necessary to bring it up to a satisfactory standard. It was impossible, in the short time allotted for the work, to secure life masks of the people, save in a very few cases, but the sculptors were required to reproduce the physical type in each instance as accurately as the available drawings and photographs would hermit. Especial effort was made to give a correct impression of the group as a whole, rather than to present portraits of individuals, which can be better presented in other ways. Life masks, as ordinarily taken, convey no clear notion of the people. The faces are distorted and expressionless, the eyes are closed, and the lips compressed. Like the, ordinary studio photograph of primitive sitters, the mask serves chiefly to misrepresent the native countenance and disposition; besides, the individual face is not necessarily a good type of a group. Good types may, however, be worked out by the skilful artist and sculptor, who alone can adequately present these little-understood people as they really are and with reasonable unity in pose and expression.

The lack of appropriate and complete costumes, especially for the women and children, proved the most serious drawback. An attempt was made to remedy this by sending collectors to the field, but only one of four expeditious sent out returned in time to be of service in the preparation of this exhibit.

It is well understood that for exposition purposes the assemblage of family groups - or larger units - of the living peoples would be far superior to lay-figure exhibits. The real family, clothed in its own costumes, engaged in its own occupations, and surrounded by its actual belongings, would form the best possible inustration of a people; but such an exhibit, covering the whole American field, would require much time for its preparation as well as the expenditure of large, scans of money. Furthermore, from the museum point of view, the creation of a set of adequate and artistic lay-figure groups forms a permanent exhibit which, set up in the museum, continues to please and instruct for generations; whereas the real people, howsoever well assembled, must scatter at the close, of the exposition, and nothing is left for future museum display. Such assemblages of our native peoples as those of the World's Columbian, the Trans-Mississippi and the Pan-American expositions are highly interesting, and instructive, but their influence is soon lost, since they reach only the audience of the season.

Future expositions may essay the bringing together of living representatives of type tribes, scientifically presented and free from the commercial incubus, but to secure satisfactory results the work must needs begin not leas than two years before the opening of the exposition.

The family groups and other lay figures included in the present exhibit are allotted for such as could he brought together in the short period preparation, and represent the following tribes:

1. North Greenland Eskimo.

2. Eastern Eskimo.

3. Alaskan Eskimo.

4. Chilkat Indiana, Alaska.

5. Hupa Indians, California.

6. Sioux Indians the Great Plains.

7. Navaho Indiana, the arid region.

8. Zuni Indians, the arid region.

9. Cocopa Indians, Sonora, Mexico.

10. Maya-Quiche Indicans, Guatemala.

11a. Zapotec Indian woman, Oaxaca, Mexico.

11b. Jivaro Indian man, Brazil.

11c. Piro Indian man, Brazil.

12. Tehuelche Indians, Patagonia.

Exhibits 2, 3, and 11 of this series were not completed as family groups and remain assemblages of independent figures simply.

Description of the Groups

The first exhibit of the series beginning at the north, shows an Eskimo family of Smith Sound, northwestern Greenland. These are the most, northern inhabitants of the world known. On account of the prevalence of ice the year round they make little use of the kaiak, or skin boat, employed so constantly by the more southern Eskimo, using the dog sled for transportation. Their clothing is of skins of the seal, reindeer, birds, and dogs, and their houses are often built of snow. Their activities are nearly all associated with the mere struggle for existence.

This group represents a family as it might appear in the spring, moving across the ice fields. The young man has succeeded in clubbing a small seal, and having called on the sledge party to haul it home is laughed at by the elder man, who tells he should have carried it oil his back.

This episode is chosen with the view of illustrating the noteworthy fact that these farthest-north people are exceptionally cheerful in disposition, notwithstanding the rigor of the climate and the hardships of their life. The woman, who carries a babe in her hood, is about to help attach the seal to the sledge, and the girl, who plays with the dogs, and the boy, who clings to the back of the sledge, are not insensible to the pleasantries of the occasion.

In

the second exhibit, three south Greenland figures take the place of the family

group, which could not he completed in time. They represent the Eskimo who

inhabit Greenland, the shores of northern Labrador, and Hudson Bay adjoining.

The figure at the right is that of a young woman of southwestern Greenland,

her dress resembling that of a Lapp. Her people have been under instruction

of Moravian missionaries for generations. The middle figure represents the

native right-hand man of the intrepid whalers, who before the discovery of

coal oil ransacked Hudson Bay for oil and baleen. The woman at the left is

front Ungava Bay, and is dressed in aboriginal costume of reindeer fur, little,

modified by outside influences. Her loose, roomy garments correspond with

those figured by the early Voyagers. In her left hand she carries a large

wooden plate, while the right is lifted to case the headband which passes

around the forehead, sustaining the babe, held in the hood behind. The eastern

Eskimo are especially interesting on account of their association with the

exploring expeditions sent out in the last century to seareh for the northwest

passage and the North Pole.

In

the second exhibit, three south Greenland figures take the place of the family

group, which could not he completed in time. They represent the Eskimo who

inhabit Greenland, the shores of northern Labrador, and Hudson Bay adjoining.

The figure at the right is that of a young woman of southwestern Greenland,

her dress resembling that of a Lapp. Her people have been under instruction

of Moravian missionaries for generations. The middle figure represents the

native right-hand man of the intrepid whalers, who before the discovery of

coal oil ransacked Hudson Bay for oil and baleen. The woman at the left is

front Ungava Bay, and is dressed in aboriginal costume of reindeer fur, little,

modified by outside influences. Her loose, roomy garments correspond with

those figured by the early Voyagers. In her left hand she carries a large

wooden plate, while the right is lifted to case the headband which passes

around the forehead, sustaining the babe, held in the hood behind. The eastern

Eskimo are especially interesting on account of their association with the

exploring expeditions sent out in the last century to seareh for the northwest

passage and the North Pole.

The third case contains three lay figures of the western Eskimo, who inhabit the shores of the northwestern seas from the mouth of the Mackenzie River around Alaska to Mount St. Elias. Their mode of dress and living varies according to the animals on which they depend and the contact hey have had with other race. In this group win be seen a woman and child from the Mackenzie River district dressed in caribou skins, a man from about Norton Sound holding his barbed harpoon, and a woman front Bristol Bay clad in marmot skins. The Mackenzie and Bristol Bay people are out of touch with the great fleet of whalers, and their arts are not greatly modified, but the Norton Sound Eskimo have been under instruction of Russians and Americans for more than a hundred years.

The fourth group inustrate

the Chilkat Indian family of the North Pacific ethnic province. They live

on Lynn Canal, or channel, in  southeastern

Alaska, and belong to the same family as the better-known Tlinkits. They are

selected to stand as a type of the region because they are the only tribe

that stin retains in a measure the aboriginal costume. They are in commercial

contact with the Athapascan family over the mountains to the east, from whom

they obtain horns and wool of the aretic goat. The wool is used in making

the famous Chilkat blankets, which are not woven in a loom but the foundation

strands are suspended from a bar of wood and fall free at the ends or are

tied up in bundles. The figures of the design are inserted separately, as

in a gobelin tapestry. The men of the tribe carve the utensils and ceremonial

objects from wood and horn. In this group we see, sitting on the floor, a

man carving it wooden mask. He is dressed in a buckskin suit whose decorations

show contact with the Tinne tribes over the mountains. The woman opposite

is engaged in making a basket, with her babe in its cradle by her side. Standing

behind is a young girl offering food in a carved wooden dish to a man who

wears one of the fine Chilkat blankets over his shoulders. Usually the food

is placed on the ground and the men sit or squat about it, the women eating

separately. The costumes are of buckskin made in the primitive style and numerous

articles pertaining to the household or employed in the arts are scattered

about the gronp.

southeastern

Alaska, and belong to the same family as the better-known Tlinkits. They are

selected to stand as a type of the region because they are the only tribe

that stin retains in a measure the aboriginal costume. They are in commercial

contact with the Athapascan family over the mountains to the east, from whom

they obtain horns and wool of the aretic goat. The wool is used in making

the famous Chilkat blankets, which are not woven in a loom but the foundation

strands are suspended from a bar of wood and fall free at the ends or are

tied up in bundles. The figures of the design are inserted separately, as

in a gobelin tapestry. The men of the tribe carve the utensils and ceremonial

objects from wood and horn. In this group we see, sitting on the floor, a

man carving it wooden mask. He is dressed in a buckskin suit whose decorations

show contact with the Tinne tribes over the mountains. The woman opposite

is engaged in making a basket, with her babe in its cradle by her side. Standing

behind is a young girl offering food in a carved wooden dish to a man who

wears one of the fine Chilkat blankets over his shoulders. Usually the food

is placed on the ground and the men sit or squat about it, the women eating

separately. The costumes are of buckskin made in the primitive style and numerous

articles pertaining to the household or employed in the arts are scattered

about the gronp.

The

Hupa Indians, shown in the fifth group, inhabit the valley of the same name

in northwestern California. They represent in this series of family groups

the mixed tribes of California and Oregon. Physically the Hupa stand between

the large-bodied Sioux and the under-sized Pueblo Indians. In language they

belong to the Athapascan family in common with the Tinne of Canada and the

Apache and Navaho of Arizona. They live on a mixed diet of meat, fish, and

acorns; dress in deerskin, and are fond of personal ornament. Their better

houses are of cedar planks and the floor is slightly sunken beneath the surface

of the ground. An important industry among them is the harvesting, transporting,

storing, and mining of acorns, together with the preparation of food from

the meal.

The

Hupa Indians, shown in the fifth group, inhabit the valley of the same name

in northwestern California. They represent in this series of family groups

the mixed tribes of California and Oregon. Physically the Hupa stand between

the large-bodied Sioux and the under-sized Pueblo Indians. In language they

belong to the Athapascan family in common with the Tinne of Canada and the

Apache and Navaho of Arizona. They live on a mixed diet of meat, fish, and

acorns; dress in deerskin, and are fond of personal ornament. Their better

houses are of cedar planks and the floor is slightly sunken beneath the surface

of the ground. An important industry among them is the harvesting, transporting,

storing, and mining of acorns, together with the preparation of food from

the meal.

In this group the man is making fire with the twirling drill, the standing woman carries a load of acorns just gathered, and the sitting woman is pulverizing acorns in a stone mortar surmounted by a basket hopper held in place by the miner's knees.

Group 6 illustrates a Sioux

family, which is taken as a type of the inhabitants of the (treat Plains ethnic

province. It is on these  plains

that the Sioux, Algonkin, and Kiowa developed their peculiar culture. The

activities of all these tribes were created and fostered by the buffalo -

including their food, dress, tents, tools, utensils, arts, industries, social

life, lore, and religion. In the group appear the man, who is the hunter,

returning with a trophy of the chase; the wife, who is butcher, tanner, clothier,

purveyor, pack animal, and general drudge, is dressing a hide; the young girl

is, beading a moccasin for her sister, who is interested in the work. The

smaller boy, with bow and arrow, welcomes the father. The tribes of the Great

Plains are thought to have been in early times sedentary, but the acquisition

of the horse and the gun fostered a more roving life.

plains

that the Sioux, Algonkin, and Kiowa developed their peculiar culture. The

activities of all these tribes were created and fostered by the buffalo -

including their food, dress, tents, tools, utensils, arts, industries, social

life, lore, and religion. In the group appear the man, who is the hunter,

returning with a trophy of the chase; the wife, who is butcher, tanner, clothier,

purveyor, pack animal, and general drudge, is dressing a hide; the young girl

is, beading a moccasin for her sister, who is interested in the work. The

smaller boy, with bow and arrow, welcomes the father. The tribes of the Great

Plains are thought to have been in early times sedentary, but the acquisition

of the horse and the gun fostered a more roving life.

Group

7 illustrates a Navaho Indian family of the Pueblo province. They belong to

the Athapascan family, whose home is in northwestern Canada and central Alaska.

They are among the most interesting tribes of the United States since, under

Spanish direction, they laid aside their wild hunting habits, becoming herdsmen

of' sheep and other domestic is animals and learning to weave and to work

in metals. Their kinsmen, the Apache, on the other hand, fled from the conquerors

and remained little affected by civilization down to the present time.

Group

7 illustrates a Navaho Indian family of the Pueblo province. They belong to

the Athapascan family, whose home is in northwestern Canada and central Alaska.

They are among the most interesting tribes of the United States since, under

Spanish direction, they laid aside their wild hunting habits, becoming herdsmen

of' sheep and other domestic is animals and learning to weave and to work

in metals. Their kinsmen, the Apache, on the other hand, fled from the conquerors

and remained little affected by civilization down to the present time.

The group includes three figures. The man is at work with modern implements of iron, shaping the silver ornaments so skillfully wrought by the workmen of his tribe. Two women are engaged in the must notable industry of this people, the spinning of yarn froth native wool and the weaving of blankets.

The Zuni Indians, represented

in the eighth family group, live in pueblos on the tablelands of western New

Mexico and stand for  the

sedentary town-building type of the Pueblo region. They were visited at the

beginning of the 16th century by the earliest Spanish explorers, and have

been a subject of study by ethnologists for many years. They dress in woolen

clothing, are agriculturists as well as herdsmen, and make excellent belts,

blankets, and pottery. At the same time they are devoted to their ancient

religion.

the

sedentary town-building type of the Pueblo region. They were visited at the

beginning of the 16th century by the earliest Spanish explorers, and have

been a subject of study by ethnologists for many years. They dress in woolen

clothing, are agriculturists as well as herdsmen, and make excellent belts,

blankets, and pottery. At the same time they are devoted to their ancient

religion.

This group includes in the foreground a young women engaged in weaving one of the artistic belts used for the waist. At the right is seated an old truth occupied in drilling a bit of stone with the ordinary pump drill. His dress is that worn during the Spanish period. Near the middle of the group stands a young girl in the usual costume who has just returned from the spring, bearing upon her head a water vessel. On the right are two children interested in their frugal meal.

The

Cocopa Indian family, shown in group 9, represents the Sonoran ethnic province.

They occupy the lover valley of the Colorado River, Mexico, from the international

boundary to the head of the Gulf of California. Although they were visited

by Spaniards in 1540, and have been in contact with the Caucasian race for

two hundred years, they retained their primitive traits up to about 1890.

They subsist largely by means of agriculture, feeding partly on game and fish,

with various seeds, roots, and fruits. They dwell in scattered settlements,

usually of one to half a dozen houses, which pertain to a family or clan.

Little costume is used, the men until recently habitually wearing skins and

the women petticoats of the inner bark of willow, as seen in the illustration.

Their faces are habitually painted, and they are tattooed moderately.

The

Cocopa Indian family, shown in group 9, represents the Sonoran ethnic province.

They occupy the lover valley of the Colorado River, Mexico, from the international

boundary to the head of the Gulf of California. Although they were visited

by Spaniards in 1540, and have been in contact with the Caucasian race for

two hundred years, they retained their primitive traits up to about 1890.

They subsist largely by means of agriculture, feeding partly on game and fish,

with various seeds, roots, and fruits. They dwell in scattered settlements,

usually of one to half a dozen houses, which pertain to a family or clan.

Little costume is used, the men until recently habitually wearing skins and

the women petticoats of the inner bark of willow, as seen in the illustration.

Their faces are habitually painted, and they are tattooed moderately.

The group includes five figures. A young man with bow and arrow is engaged in teaching a boy to shoot; the woman is pounding corn in a wooden mortar, and the young girl carries the babe and concerns herself with the how practice of the boy.

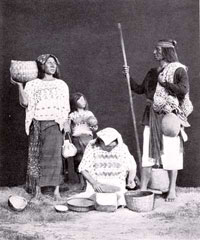

The

tenth family group shows the Maya-Quiche of Guatemala. These people occupy

also parts of Chiapas and a small area in western Honduras; at one time they

were the most highly cultured of all the native peoples of the Western Hemisphere.

They had an artificial basis of food supply, dressed in delicate fabrics,

and were capable of erecting vast terraces and stepped pyramids surmounted

with buildings adorned with sculptures and paintings. They were of moderate

stature, not warlike, but industrial, and the sculptures and paintings revealing

their religion are remarkably free from bloody scenes. They number in Central

America, at present, several hundreds of thousands. The family group here

presented includes the man with staff and bearing a net filled with fruit,

one woman working at the mill, a second woman carrying a basket of fruit in

her right hand and a gourd bowl in the left, while the girl walks by her mother,

and holds it decorated globular, gourd vessel.

The

tenth family group shows the Maya-Quiche of Guatemala. These people occupy

also parts of Chiapas and a small area in western Honduras; at one time they

were the most highly cultured of all the native peoples of the Western Hemisphere.

They had an artificial basis of food supply, dressed in delicate fabrics,

and were capable of erecting vast terraces and stepped pyramids surmounted

with buildings adorned with sculptures and paintings. They were of moderate

stature, not warlike, but industrial, and the sculptures and paintings revealing

their religion are remarkably free from bloody scenes. They number in Central

America, at present, several hundreds of thousands. The family group here

presented includes the man with staff and bearing a net filled with fruit,

one woman working at the mill, a second woman carrying a basket of fruit in

her right hand and a gourd bowl in the left, while the girl walks by her mother,

and holds it decorated globular, gourd vessel.

The

eleventh group consists of three figures, a woman of Oaxaca, southern Mexico,

and two men, representing the Piro and Jivaro tribes of the headwaters of

the Amazon. The Oaxacan woman is dressed in a skirt of striped native-woven

cloth, held by a belt. The upper part of the body is covered with a tastefully

decorated tunic. The head is protected by a long sash or rebozo. She carries

in her left hand a red earthen drinking cup and in her right two gourd vessels.

The third figure is a Piro man, Arawakan family, head of the Ucayle, interesting

because tribes speaking the same language were met by Columbus on his first

voyage to America. He wears a tunic of native make, embellished with artistic

patterns, and confined only by a sash of beads decorated with skins of birds

passing over the right shoulder and beneath the left arm. The headdress consists

of a bark band in which are set three bird plumes. He holds in both hands

a ceremonial baton.

The

eleventh group consists of three figures, a woman of Oaxaca, southern Mexico,

and two men, representing the Piro and Jivaro tribes of the headwaters of

the Amazon. The Oaxacan woman is dressed in a skirt of striped native-woven

cloth, held by a belt. The upper part of the body is covered with a tastefully

decorated tunic. The head is protected by a long sash or rebozo. She carries

in her left hand a red earthen drinking cup and in her right two gourd vessels.

The third figure is a Piro man, Arawakan family, head of the Ucayle, interesting

because tribes speaking the same language were met by Columbus on his first

voyage to America. He wears a tunic of native make, embellished with artistic

patterns, and confined only by a sash of beads decorated with skins of birds

passing over the right shoulder and beneath the left arm. The headdress consists

of a bark band in which are set three bird plumes. He holds in both hands

a ceremonial baton.

The Jivaro man lives on the headwaters of the river Maranon. He wears a tasteful and brilliant feather skirt and headdress, ornaments of teeth, beetle wings, and seeds. This tribe, one of the most forceful and independent in South America, preserve the dried heads of their enemies.

The

Patagonians, group 12, taken as a type of the far southern tribes, apply to

call themselves the name Tzoneca, but their neighbors call them Tehuelche,

or southerners. They live on the plains and desert areas of southern Patagonia,

and all of the arts of their lives grow out of the region. They dress in the

skins of animals. Their rude tents, or toldos are made from the hides of the

same animals. Their furniture, food, and arts are occasioned by the same environment.

Living on animal diet, they resemble the Plains Indians of the United States,

being tall, bony, and athletic. When the Spaniards had introduced the horse

into America it took kindly to these grassy plains, and the Indians changed

their arts to adapt them to this new domestic animal. On horseback they hunt

the guanaco, the American ostrich, and various other animals.

The

Patagonians, group 12, taken as a type of the far southern tribes, apply to

call themselves the name Tzoneca, but their neighbors call them Tehuelche,

or southerners. They live on the plains and desert areas of southern Patagonia,

and all of the arts of their lives grow out of the region. They dress in the

skins of animals. Their rude tents, or toldos are made from the hides of the

same animals. Their furniture, food, and arts are occasioned by the same environment.

Living on animal diet, they resemble the Plains Indians of the United States,

being tall, bony, and athletic. When the Spaniards had introduced the horse

into America it took kindly to these grassy plains, and the Indians changed

their arts to adapt them to this new domestic animal. On horseback they hunt

the guanaco, the American ostrich, and various other animals.

In the group the family is on the point of breaking camp. The man, wearing a skunk-skin robe, with Bolas in hand, is ready to mount his horse. One woman has already mounted, and the boy assists in completing her outfit. The second woman is rolling up skin robes of the household, while the little girl halters the pet ostrich, and the babe sleeps in its novel cradle.

Go on to the "Dwelling Models" of these peoples